The Emperor's new COVIDSafe App

The COVIDSafe app is starting to bear an uncanny resemblance to "The Emperor's New Clothes", and a fatal flaw in the system shows why.

"The Emperor's New Clothes" is a short tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, about two weavers who promise an emperor a new suit of clothes that they say is invisible to those who are unfit for their positions, stupid, or incompetent – while in reality, they make no clothes at all, making everyone believe the clothes are invisible to them.

As Scott Morrison steps out in his invisible COVIDSafe robes, urging Australians to take up his new fashion, evidence is rapidly emerging that his imagined protective threads have a critical, unsolvable flaw: Bluetooth signals can't be used to reliably determine distance between two phones.

This shocking revelation, understood by the tech community since forever (where are all the Bluetooth measuring devices in Bunnings?), highlights how COVIDSafe is political theatre for a federal government keen to justify their lurch to a premature re-opening of society (with all the inevitable increases in COVID-19 outbreaks this entails), instead of an elimination goal outlined by Australia's Group of Eight Universities – a goal they find could deliver a 50% greater economic boost.

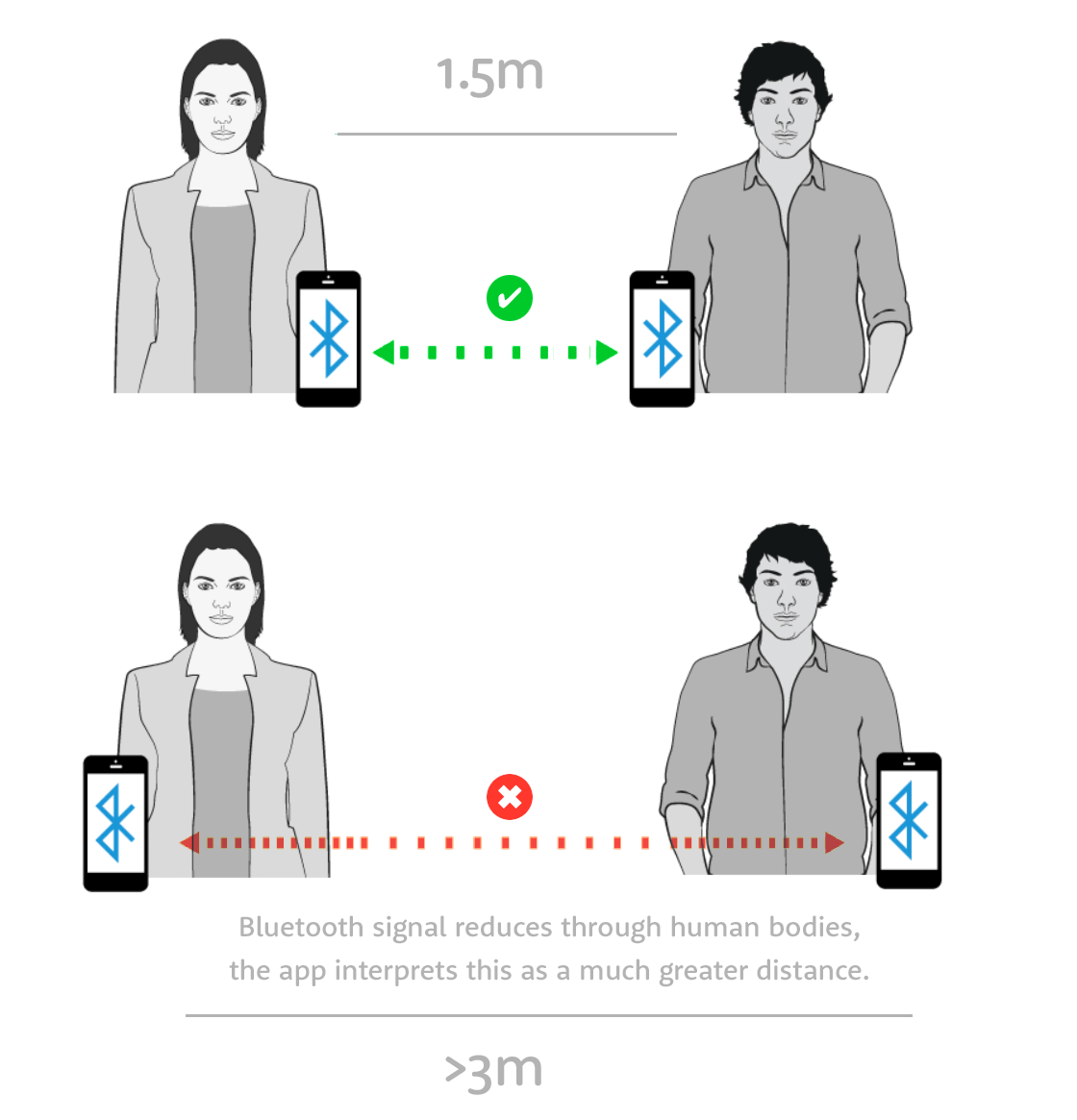

It's deceptively pitched as an app that will keep you safe (it's in the name, after all), and also one which will only register contacts you've been within 1.5 metres of for at least 15 minutes. But Bluetooth experts know the technology can do nothing of the sort:

The COVIDSafe app is utterly blind to the environmental context you are in, unable to record anything other than the other phone's model and signal strength.

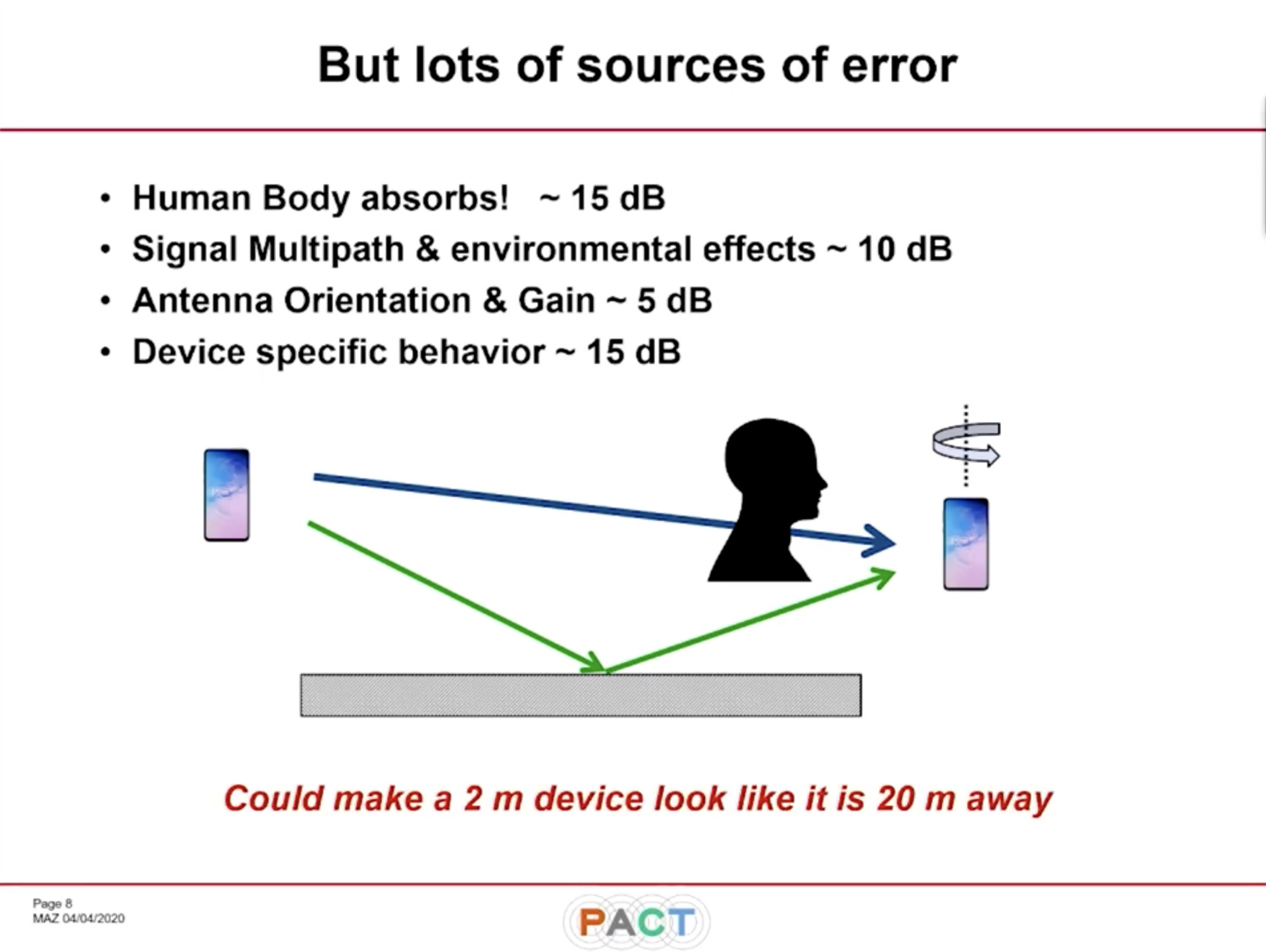

As the below slide demonstrates, signal strength is significantly impacted by human bodies, hardware, device rotation, and environmental factors like walls and floors – to the point it is basically impossible to estimate distance reliably in dynamic, real-world environments.

These flaws are not just theoretical, as one Australian researcher recently discovered:

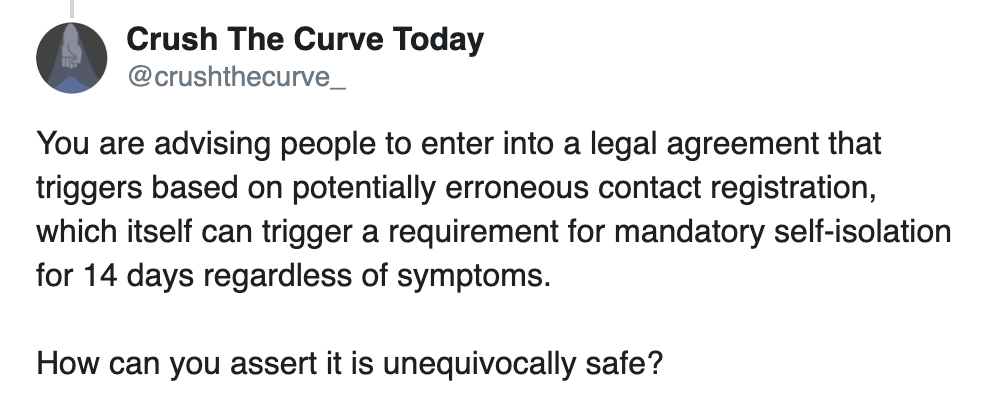

The CovidSafe app works well if you are not using it to estimate distance between two phones for epidemiological reasons.#Covid_19australia https://t.co/KUG07iku9m

— Crush The Curve Today (@crushthecurve_) May 5, 2020

This brief technical exploration revealed the likelihood of contacts being picked up in entirely separate rooms, and even rooms on different floors. (Not a problem, of course, in suburbs full of sprawling estates, but something to consider in lower-quality, higher-density housing estates, which raises important social equity questions).

The author of the tweet, Jim Mussared, has been undertaking an evaluation of numerous defects in COVIDSafe and documenting these in a public report. Part of that report deals with issues around Bluetooth proximity estimates, revealing that the Singapore team use the model of the phone to try to 'guess' the distance of each registered contact (because every phone is different), to which Mussared responds:

This calibration is extremely dubious but the authors have published details about their methodology. My own research in this area and practical experience suggests that this is highly unlikely to provide useful results.

This is not a new revelation either. Here's former US FTC CTO and Obama Whitehouse senior advisor Ashkan Soltani:

This type of approach is likely to generate significant FALSE POSITIVES and FALSE NEGATIVES -- which is highly problematic when this data is (eventually) used to make decisions that will affect citizen's freedoms -- voluntarily or not.

— ashkan soltani (@ashk4n) April 10, 2020

In fact numerous individuals and institutions have concluded Bluetooth contact tracing just won't work, from leading international security voices like Bruce Schneier ("Me on Covid-19 tracing apps") through to institutions like the Margolis Center for Health Policy at Duke University, who concluded that:

Cell phone-based apps recording proximity events between individuals are unlikely to have adequate discriminating ability or adoption to achieve public health utility

Given this widely-understood fatal flaw, why do we see full-throated cheering by an exclusive group of privileged tech voices in Australia, declaring COVIDSafe unequivocally safe?

Why do they act as the two weavers in that classic tale of 'The Emperor's New Clothes', convincing Emperor Morrison, and Australia, that the robes are just fine?

It's hard to say, but some have speculated about fuzzy networks of influence and consideration, that might lead people to get on board with little thought to deeper issues:

Should be noted some techbros have big clients in govt. 👀

— 𝙽𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝙲𝚘𝚌𝚑𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚎 (@natecochrane) May 3, 2020

If you're part of the emperor's retinue in some way (or just wanting to score a few easy political points, build a media profile, or carry the torch for tech solutionism) then maybe maintaining privilege in a system is the priority (subconscious or otherwise)?

Is that unfair commentary? Look for any analysis on the political dimension of Morrison's push from these prominent supportive Australian tech voices, and in fact any effort to consider the real-life consequences of a faulty proximity-detection system. Can you find any?

We've previously explored the issue of false positives in-depth, and there are potential real-world consequences that less technical people do not fully understand.

Asserting a position of deep technical expertise and knowledge to convince less-informed citizens to enter into legal agreements with potentially severe consequences is an extraordinarily reckless act.

Especially when you consider we have no evidence to prove the accuracy, efficacy and safety of this kind of system – just preliminary and inconclusive research from Singapore which ends in a plea for hardware manufacturers to provide more data.

Can you imagine that lack of academic rigour passing muster in serious sciences?

Anybody know if the #covidsafe app has been registered with the @TGAgovau as a medical device?

— Elen Shute (@LoneRangifer) May 2, 2020

Does it meet the criteria for being a medical device by being used for the purpose of "diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease"?https://t.co/PIqST739hZ

And yet here we are.

An app that is useless for accurately determining proximity, but one where we can only determine just how useless it is once the government publishes the algorithm used to guesstimate proximity from citizens data.

Wouldn't you think that if this is a key aspect of the system, then that needs to be published before any endorsements could be solicited or proffered?

In fact publishing this code, and detailed evidence to prove the system works in the real world, is the first action civil society should be demanding of the government. If the system doesn't work – or worse – what does it matter if it is secure, currently private or otherwise all-above-board?

Bending physics to Morrison's will might be tricky however. But as with Prime Minister Turnbull's declaration that the laws of mathematics do not apply in Australia, perhaps we'll see a similar declaration from Morrison: that the laws of physics, and indeed logic, do not apply 'Down Under'.

Meanwhile the app fails in many more fundamental ways, including reports of it interfering with diabetes glucose-monitoring apps and Bluetooth hearing aids.

***Important information for CGM Users***

— Diabetes Australia (@DiabetesAus) April 30, 2020

We have received reports from a number of people with diabetes who have downloaded the Australian Government COVIDSafe app to their smartphone and have experienced connection problems with their continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) apps.

These potentially fatal issues with the system appear invisible to Emperor Morrison and his coterie of unaware or uninterested boosters. He urges Australia to don similar robes, proclaiming the fashion is a 'ticket to freedom' and, more ominously, a 'passport'.

Yet the feigned seriousness of his health initiative is unwittingly revealed in the national obsession he encourages with 'download' numbers – a vanity metric anyone in the industry knows is as useless as this app.

A 'Daily Active Users' number (DAU) is what matters if there were a genuine interest in estimating the potential efficacy of a system which depends on many using it, but of course there isn't.

If they were serious about estimating public health utility then Daily Active Users (DAU) would be the metric to focus on, not the vanity metric of downloads.

— Crush The Curve Today (@crushthecurve_) May 5, 2020

It is an unserious, highly political and extremely manipulative program so there should be no reason to place any trust.

Just as there's no serious interest in system efficacy, our tech weavers and Emperor Morrison show no interest in all those who get unnecessarily caught up in a primitive, Bluetooth web which can legally compel 14 days of real, home-bound isolation.

Should it be any surprise that voices which show no interest in the destructive power of atrocious technology systems such as robodebt would show zero interest in the threat of roboisolation?

Step aside #robodebt, there might be a new term on the horizon.

— Crush The Curve Today (@crushthecurve_) May 5, 2020

The wildly inaccurate bluetooth readings from CovidSafe, coupled with a potential legal requirement to isolate at home for 14-days, sets marginalised groups up for:

👉 #roboisolationhttps://t.co/F5KCO0jRqz

To paper over their poor analysis and malpractice, a kind of Noblesse Oblige is conjured up, as if these far-seeing tech seers are guided by their superior wisdom and motivated by the life-saving potential of a broken app.

Yet app-boosterism involves buying into a flawed right-wing belief that giving up on elimination as the goal is reasonable, and accepting major new outbreaks is the unavoidable price to pay for a fast and stable economic recovery.

The awful truth is this app could kill many more than it saves – while delivering very short lived economic benefits (for some) – simply because it provides political camouflage for a dangerous right-wing agenda (and one where a side-effect of normalising authoritarian tech is simply a welcome cherry-on-top)

Maybe we should all think twice before donning the Emperor's New Clothes?

If you're interested in further thoughts on COVIDSafe, we've got a three-part series that asks, funnily enough, three important questions:

- Do we have a current, or future, problem with contact tracing?

- Does digital contact tracing solve it?

- Does this app in particular solve it, without creating more harm than good? (A deeper exploration of these issues, not yet released).

Otherwise if you're riled about the situation with schools in Australia we can certainly recommend School's In: Journalism As Government Public Relations.